We Ever Hear Surf Music Again

| "Third Stone from the Sun" | |

|---|---|

| Song past the Jimi Hendrix Experience | |

| from the album Are Y'all Experienced | |

| Released |

|

| Recorded | London, Jan & Apr 1967 |

| Genre |

|

| Length | vi:30 [ane] |

| Label |

|

| Songwriter(due south) | Jimi Hendrix |

| Producer(southward) | Chas Chandler |

"Tertiary Stone from the Sun" (or "3rd Stone from the Sun") is a mostly instrumental composition by American musician Jimi Hendrix. It incorporates several musical approaches, including jazz and psychedelic rock, with brief spoken passages. The title reflects Hendrix's involvement in scientific discipline fiction and is a reference to Earth in its position as the tertiary planet away from the sun in the solar system.

Hendrix adult elements of the piece prior to forming his group, the Jimi Hendrix Experience. The Experience recorded versions as early as December 1966, and, in 1967, it was included on their debut album Are You lot Experienced. Several artists have recorded renditions and others accept adapted the guitar melody line for other songs.

Background [edit]

In the summertime of 1966, Hendrix relocated to New York City's Greenwich Village. At that place he explored a stone sound exterior of the musical confines of the Harlem rhythm and dejection scene. While performing with his group Jimmy James and the Blue Flames at the Cafe Wha?, Hendrix played elements or early on versions of "Third Stone from the Lord's day".[2] [3] [4] He connected to develop information technology after moving to England with new managing director Chas Chandler. The two shared an involvement in science fiction writing,[5] including that of American writer Philip Jose Farmer.[a] Chandler recalled:

I had dozens of science fiction books at home ... The kickoff ane Jimi read was Globe Abides. It wasn't a Wink Gordon type, it's an end-of-the-world, new first, disaster-type story. He started reading through them all. That where 'Third Stone from the Sun' and 'Up from the Skies' came from.[7]

Music journalist Charles Shaar Murray associates information technology with the "hazy cosmic jive direct out of the Sun Ra science fiction textbook."[8] Hendrix chronicler Harry Shapiro suggests that his reference of a hen may take been inspired past "Ain't Nobody Hither only Us Chickens", a bound dejection song past Louis Jordan.[ix] Hashemite kingdom of jordan's song was 1 of the biggest hits of 1946 and was popular with rhythm and blues bands in Seattle, where Hendrix grew up and first performed.[9]

Composition [edit]

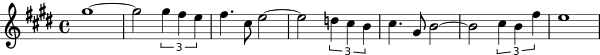

Hendrix biographer Keith Shadwick describes "3rd Stone from the Sun" as "a structured group performance" equanimous of several identifiable passages or sections with further subdivisions.[x]The first section opens with guitar chording, which Murray notes as "sliding major ninth ... arpeggiated chords and Coltranoid mock-orientalisms" with Mitch Mitchell's Elvin Jones-influenced drumming.[8] Afterwards several bars of the intro, Hendrix moves to a Wes Montgomery-way octave guitar melody line.[10] It is one of Hendrix's most recognizable guitar figures and is notated in common or 4/four time time in the primal of E:

Several writers have noted the jazz influences in the commencement section.[11] [12] [10] Still, Shadwick points out that "at no point does the band sound merely like a grouping of musicians imitating other styles. They accept their own musical identity."[10] Midway, Hendrix adds a bluesy guitar improvisation office with Mitchell and Redding switching to a more than standard rock rhythm backing, before returning to the guitar melody.[8] [10]

Around 2:thirty, Hendrix abruptly changes direction with a vibrato arm dive, which sets the stage for the 2nd section and his feedback-laden guitar improvisations.[8] Music critic Richie Unterberger described information technology as an "instrumental freak-out jam"[thirteen] and "a tour de force of psychedelic guitar".[eleven] Redding anchors the section with a 3-notation bass ostinato while Mitchell provides rhythmic improvisation.[10] Shadwick describes Hendrix's solo:

[T]his is not an orthodox guitar solo. It is more alike to a soundscape forged from his control of amplified feedback and the way he manipulates the Stratocaster's [guitar'due south] concrete characteristics, including its switches and vibrato arm.[10]

Murray notes that he performs largely independent of rhythm, tonality, or notes and enters into pure sound, which he describes as:[eight]

[South]creams, whinnies, sirens, revving motorcycle engines, burglar alarms, explosions, droning buzz-saws, subway trains, the rattling of disintegrating industrial machinery, the howl and the whine of mortar shells.[viii]

To wind down, Hendrix returns to the guitar melody line, although with more baloney and vibrato.[x] The instrumental concludes with "what was peradventure the Feel'due south version of Armageddon" and a fade.[ten]

Spoken sections [edit]

Spoken sections, oft slowed downwardly and otherwise sonically manipulated, run intermittently throughout the piece.[11] Hendrix and Chandler recorded the dialogue, which parodies a science fiction scenario. Shadwick notes the joking nature,[10] although Hendrix described it thing-of-factly:

These guys come up from another planet, you know ... they discover Earth for a while and they think the smartest animal on the whole Earth is chickens [and] there's nothing else there, and then they just accident information technology upwards at the stop.[9]

The dialogue opens with a mock advice betwixt conflicting space explorers slowed to half-speed, which makes it mostly unintelligible.[9]

Hendrix: Star fleet to sentinel ship, please give your position. Over.

Chandler: I am in orbit effectually the 3rd planet of star called the Dominicus. Over.

Hendrix: Yous mean it's the Earth? Over.

Chandler: Positive. It is known to accept some form of intelligent species. Over.

Hendrix: I think nosotros should take a look.[14]

The alien visitor, voiced by Hendrix at normal speed, makes some observations of the planet.[12] He marvels at the "purple and superior cackling hen", but dismisses the people and concludes:[6]

So to you I shall put an stop

And you lot'll never hear surf music again ...

[At one-half-speed] That sounds like a lie to me

Come on human, let'due south go home[fourteen]

Music journalist Peter Doggett notes the irony of the surf music reference.[xv] In 1970, concern manager Michael Jeffery committed Hendrix to contributing to the soundtrack for Rainbow Span; his music is heard during surfing scenes with David Nuuhiwa and others.[16] [b] Pioneer surf guitarist Dick Dale, who claimed to accept met Hendrix in Los Angeles in 1964, believed the mention was Hendrix's way of encouraging his recuperation when Dale was seriously ill.[18]

Recording [edit]

"Third Stone from the Sun" was ane of the primeval recordings attempted by the Experience.[19] They recorded a demo version at CBS studios in London on December 13, 1966.[20] All the same, because of a dispute over studio fees, information technology was left unfinished.[21] On January xi, 1967, several takes were recorded at De Lane Lea Studios in London, but a master was not realized.[22] Work on the track resumed on April four, 1967, at Olympic Studios in London.[23] Session engineer Eddie Kramer recalls that the original recording was largely abased and replaced with new overdubs.[24]

The master for the track was finally completed on April ten, 1967, also at Olympic.[23] At this session, the spoken sections and audio effects were recorded and the final audio mixing took place.[25] Several takes were required since Hendrix and Chandler were joking and laughing throughout the session.[25] Hendrix biographer and later producer John McDermott notes that it shows the camaraderie enjoyed by the two during the early days of the Feel.[five]

The instrumental makes novel use of recording and mixing. Hendrix contributed to the audio effects past moving his headphones around the microphone to alter the sound of his whispers and breathing.[25] In preparing the final mix, Kramer experimented with the rail's sound imaging or an instrument's apparent placement, merely was limited past the existing technology.[25] He later explained:

That vocal was like a watercolor painting ... to create a sense of motility within the overall sound, I pushed Mitch'southward [drummer Mitch Mitchell's] cymbals forward in the mix and panned the four tracks on the finished master. Each runway was composed of four, fairly dumbo, composite images. With iv rail recording, you were restricted to panning these multiple layers of sound, whereas now, with twenty-4 and forty-eight rails recording, what you can pan is unlimited.[25]

Releases and performances [edit]

"Third Stone from the Sun" was released on the Experience'south debut anthology, Are You Experienced. Information technology appears every bit the 3rd runway on side two of the LP record.[26] Track Records issued the anthology in the UK on May 12, 1967, using "third Rock from the Sunday" every bit the championship.[27] It also used a monaural mix, which includes an extra line, "War must be war".[28] Reprise Records issued the anthology in the US on August 23, 1967, with a stereo mix.[29]

In 1982, the instrumental was included on the UK Voodoo Chile 12-inch single[30] and the following The Singles Album (1983).[31] Information technology likewise appeared on compilations, such as Re-Experienced (1975),[32] The Essential Jimi Hendrix (1978), [33] Kiss the Heaven (1984),[31] and Voodoo Child: The Jimi Hendrix Collection (2001 Britain bonus rail). In 2000, a version with some different overdubbed dialogue (and without sound processing) was released on The Jimi Hendrix Experience boxed set.[5]

Mitchell recalled that the instrumental was only played alive occasionally.[34] A performance at Blaise's social club in London shortly after the December 1966 release of "Hey Joe"[35] was reviewed past music announcer Chris Welch for Tune Maker.[36] It was the just original slice among several songs he mentioned in the article.[36] Hendrix played some of the guitar melody line during "Spanish Castle Magic" at the Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto, Canada, shortly after his abort for drug possession on May three, 1969.[37] Hendrix biographer Steven Roby identifies a 1969 concert recording, maybe from Deutschland in January, every bit the only recorded complete performance of "Third Stone from the Dominicus".[38] None of the live recordings take been officially released.[29]

Reception and influence [edit]

Music writers take described the instrumental'due south jazz elements[11] [12] [ten] and Murray questions whether Hendrix's approach was studied or more organic.[eight] [c] Bassist Jaco Pastorius felt that Hendrix'southward touch on on jazz was obvious: "All I got to say is ... 'Third Rock from the Sun'. And for anyone who doesn't know about that by at present [1982], they should take checked Jimi out a lot earlier."[8]

According to music educator William Echard, "Third Rock from the Sunday" "closely resemble[southward] subsequently space-rock norms and was likely influential in putting these into place".[twoscore] Shadwick feels that the freak-out sections may have inspired countless less-imaginative imitators.[x] In a song review for AllMusic, Unterberger saw the potential for a more fully realized piece:

"3rd Stone from the Sunday" suffers from also much electronic trickery, likewise much convoluted ambition in its freaky turns and twists, and not plenty follow-through from the quite good guitar riffs that surface from time to time.[11]

Musicians from a variety of backgrounds have recorded versions of the instrumental.[11] A live recording by guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan appears on Live at the El Mocambo (1991 video). Music critic Bret Adams wrote in an anthology review for AllMusic, "Vaughan pays tribute to Hendrix again with 'Third Stone from the Sun'; he thrashes on his famously mangled sunburst Stratocaster and coaxes unholy noises out of information technology. It's as if Pete Townshend took possession of him in that moment."[41] The more consummate version is included on Power of Soul: A Tribute to Jimi Hendrix (2004). AllMusic's Sean Westergaard calls it "a blistering live medley of 'Lilliputian Wing' and 'Third Stone from the Dominicus'... Vaughan absolutely nails information technology. There are some flubs in his operation, but the amount of feeling he plays with easily overcomes them".[42]

The guitar melody has been quoted in a number of unlike recorded songs, such as "Infant, Delight Don't Go" (the Amboy Dukes, 1968),[xi] "Trip the light fantastic with the Devil" (Cozy Powell, 1973),[43] and "I'm As well Sexy" (Correct Said Fred, 1991),[44]

Notes [edit]

Footnotes

- ^ Hendrix and Chandler read Farmer's Night of Calorie-free, which referenced a "purplish haze".[6]

- ^ In an opening scene in Rainbow Bridge, an unidentified grapheme on horse back shoots a surfer riding his board, while Hendrix'south functioning of "Ezy Ryder" plays over the sequence.[17]

- ^ "Upwards from the Skies", from Axis: Assuming as Love, too mixes sci-fi and jazz, perhaps more than consciously in the style of Mose Allison and Grant Green.[39]

Citations

- ^ From Are You Experienced liner notes (original international Polydor edition)

- ^ McDermott, Kramer & Cox 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Shadwick 2003, pp. 77, eighty.

- ^ Roby & Schreiber 2010, p. 165.

- ^ a b c McDermott 2000, p. 20.

- ^ a b Roby & Schreiber 2010, p. 158.

- ^ McDermott, Kramer & Cox 2009, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d due east f yard h Murray 1991, p. 193.

- ^ a b c d Shapiro & Glebbeek 1991, p. 177.

- ^ a b c d e f thousand h i j k fifty Shadwick 2003, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d e f thousand Unterberger, Richie. "Jimi Hendrix/The Jimi Hendrix Feel: Third Stone from the Sun – Song Review". AllMusic . Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c Shapiro & Glebbeek 1991, p. 179.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "The Jimi Hendrix Feel/Jimi Hendrix: Are You Experienced? – Review". AllMusic . Retrieved September xx, 2016.

- ^ a b Hendrix 2003, p. 162.

- ^ Doggett 2011, eBook.

- ^ McDermott, Kramer & Cox 2009, p. 239.

- ^ Rolling Stone (August 5, 1971). "Rainbow Bridge: Hendrix in Hawaii". Rolling Stone . Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ Roby & Schreiber 2010, pp. 104–105.

- ^ McDermott, Kramer & Cox 2009, p. 27.

- ^ McDermott, Kramer & Cox 2009, pp. 26–27.

- ^ McDermott, Kramer & Cox 2009, pp. 27–28, 32.

- ^ McDermott, Kramer & Cox 2009, p. 32.

- ^ a b McDermott, Kramer & Cox 2009, pp. 44–45.

- ^ McDermott, Kramer & Cox 2009, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d due east McDermott, Kramer & Cox 2009, p. 45.

- ^ McDermott, Kramer & Cox 2009, pp. 50, 61.

- ^ Are You Experienced (Album notes). the Jimi Hendrix Experience. London: Track Records. 1967. LP Side 2 label. 612 001.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Jucha 2013, eBook.

- ^ a b Belmo & Loveless 1998, p. 472.

- ^ Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Republic of chile (Tape notes). Jimi Hendrix Experience. Polydor Records. 1982. Back cover. POSPX608.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b Shapiro & Glebbeek 1991, p. 553.

- ^ "Jimi Hendrix: Re Experienced – Overview". AllMusic . Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ Shapiro & Glebbeek 1990, p. 550. sfn error: no target: CITEREFShapiroGlebbeek1990 (help)

- ^ Mitchell & Platt 1990, p. 41.

- ^ McDermott, Kramer & Cox 2009, pp. 28, 29.

- ^ a b Black 1999, p. 68.

- ^ McDermott, Kramer & Cox 2009, p. 157.

- ^ Roby 2002, p. 200.

- ^ Shadwick 2003, p. 129.

- ^ Echard 2017, p. 207.

- ^ Adams, Bret. "Stevie Ray Vaughan & Double Trouble / Stevie Ray Vaughan: Live at the El Mocambo – Review". AllMusic . Retrieved March twenty, 2022.

- ^ Westergaard, Sean. "Various Artists: Power of Soul: A Tribute to JimiHendrix – Review". AllMusic . Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ Doggett 2011, p. 73.

- ^ Spicer 1999, p. 72.

References

- Belmo; Loveless, Steve (1998). Jimi Hendrix: Experience the Music. Burlington, Ontario: Collector'southward Guide Publishing. ISBN1-896522-45-nine.

- Black, Johnny (1999). Jimi Hendrix: The Ultimate Feel. New York City: Thunder'southward Mouth Press. ISBNane-56025-240-five.

- Doggett, Peter (2011). Jimi Hendrix: The Complete Guide To His Music. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN978-0-85712-710-5.

- Echard, William (2017). Psychedelic Popular Music: A History through Musical Topic Theory. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana Academy Press. p. v. ISBN978-0253026590.

- Hendrix, Janie (2003). Jimi Hendrix: The Lyrics. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Hal Leonard. ISBN0-634-04930-5.

- Jucha, Gary J. (2013). Jimi Hendrix FAQ: All That'due south Left to Know About the Voodoo Child. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Backbeat Books. ISBN978-1-61713-095-iii.

- McDermott, John (2000). The Jimi Hendrix Feel (Box gear up booklet). Jimi Hendrix Experience. New York Metropolis: MCA Records. 08811 23162.

- McDermott, John; Kramer, Eddie; Cox, Billy (2009). Ultimate Hendrix. New York City: Backbeat Books. ISBN978-0-87930-938-1.

- Milkowski, Pecker (2005). Jaco: The Extraordinary and Tragic Life of Jaco Pastorius. San Francisco: Backbeat Books. ISBN978-0-87930-859-9.

- Mitchell, Mitch; Platt, John (1990). Jimi Hendrix: Inside the Experience. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN978-0-312-10098-8.

- Murray, Charles Shaar (1991). Crosstown Traffic. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN0-312-06324-5.

- Roby, Steven (2002). Blackness Aureate: The Lost Archives of Jimi Hendrix. New York City: Billboard Books. ISBN0-8230-7854-Ten.

- Roby, Steven; Schreiber, Brad (2010). Becoming Jimi Hendrix. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN978-0-306-81910-0.

- Shadwick, Keith (2003). Jimi Hendrix: Musician. San Francisco: Backbeat Books. ISBN0-87930-764-one.

- Shapiro, Harry; Glebbeek, Cesar (1991). Jimi Hendrix: Electric Gypsy. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN0-312-05861-6.

- Spicer, Al (1999). Rock: 100 Essential CDs – The Rough Guide. London: Rough Guides. ISBN978-1858284903.

External links [edit]

- Stevie Ray Vaughan – "Third Stone from the Lord's day" (from Live at the El Mocambo, 1991) on Vevo

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_Stone_from_the_Sun